Excavating the Museum

Any major building project in the heart of historic Lincoln will have archaeological implications, and the building of Lincoln Museum was no exception.

The archaeological investigations were carried out before building work began, as the museum sits partially on the site of a Scheduled Ancient Monument. Planning permission required that the areas to be disturbed by the museum’s lift shafts and foundations had to be excavated, though the building was designed to minimise this impact and preserve as much surviving archaeology in situ as possible. The excavations were carried out by the Lincolnshire based company Archaeological Project Services between April and August 2003.

Introduction and historical background

The museum sits on Lincoln’s hillside, just inside the eastern defences of the lower Roman and Medieval city.

The streets surrounding the museum are of some antiquity. Flaxengate, to the west of the museum, is known to have been in existence as early as c.AD900. The earliest documentary evidence is from AD1215-1220, when it was known as ‘Haraldestigh’. It appears as ‘Flaxgate’ in 1661, and as ‘Flaxengate’ in 1831. To the east of the museum is Danesgate, which was probably laid out in the 11th century. It appears to have lost its original name of ‘Danissegate’ in the early 19th century when it became known as Bull Ring Lane, but its ancient name was revived in 1830. To the north of the museum is Danes Terrace, which seems to have come into existence at the same time as Danesgate. The street was known as ‘La Boulstak’ in AD1314, had become ‘Bull Ring Terrace’ by the 19th century, and had its modern name of Danes Terrace from 1851 onwards.

Previous excavations in the same area of the city suggested that significant Roman, Anglo-Scandinavian and Medieval archaeology would be encountered, as would the remains of the Victorian buildings (including the Manvers Arms Public House) previously occupying the site. The main evidence from each of these periods will be discussed below.

Romano-British (1st to 4th centuries AD)

The site revealed slight evidence of occupation during the early Roman period, in the form of fragments of pits and some linear features which may relate to timber buildings. The early finds included a sherd of imported Samian ware stamped with the maker’s name ‘Silvinus’, and dating to AD65-90. The early remains may relate to occupation within the legionary canabae or the civilian vicus associated with the hilltop fortress of the Ninth Legion. Further evidence of early Roman activity may have existed beyond the depth limit of the excavations.

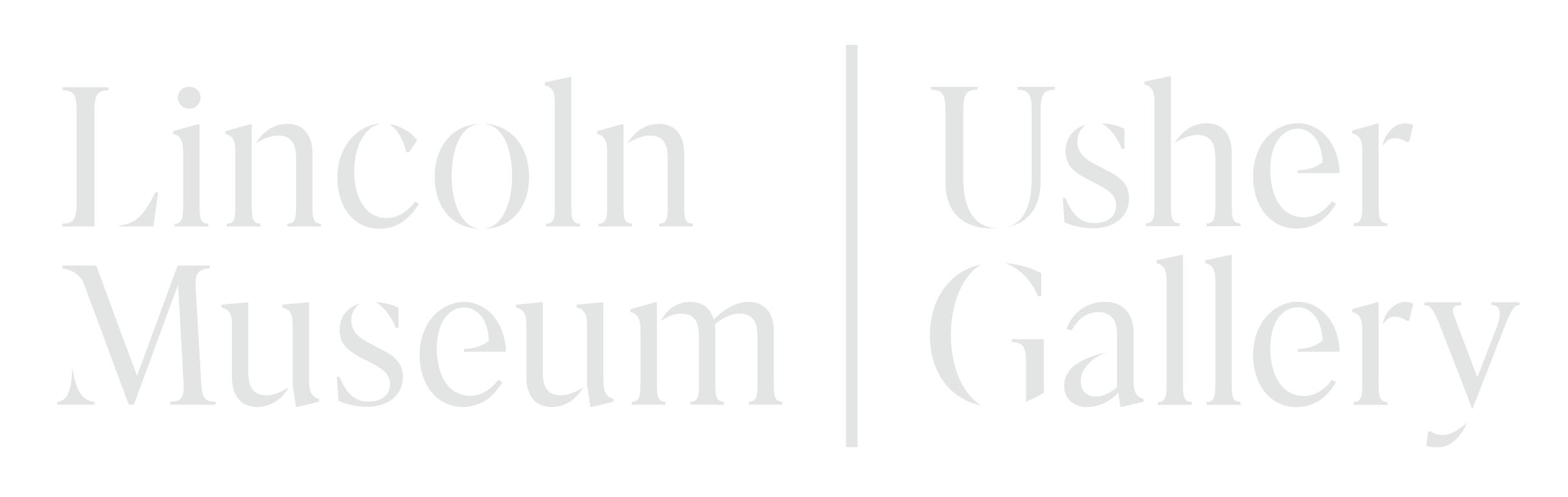

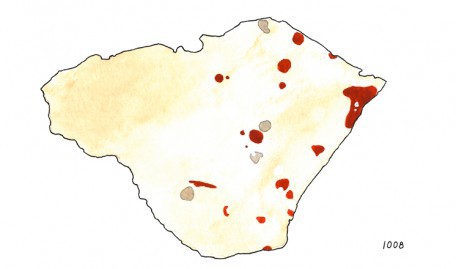

The most significant Romano-British discovery was the corner of a late Roman town house, found in the pit being dug for the museum’s goods lift. The excavation uncovered an L-shaped tessellated pavement with a red and cream chequered pattern, dating to the 4th century. The tesserae are of local limestone, with the red tesserae created by heating the stone. The corner of the mosaic displays visible wear, showing how the Roman occupants cut off the corner of the corridor as they walked.

Mosaic pavements such as this are rare discoveries within the walled Roman city, and this represents the largest mosaic discovered since the 19th century. Simple chequered mosaics are known from numerous other sites in Britain, including in uphill Lincoln. The presence of such a corridor strongly suggests that other mosaics existed in the house, outside the limits of the excavation and now preserved in situ beneath the museum building.

The mosaic can now be seen displayed underneath the floor of the museum’s archaeology gallery.

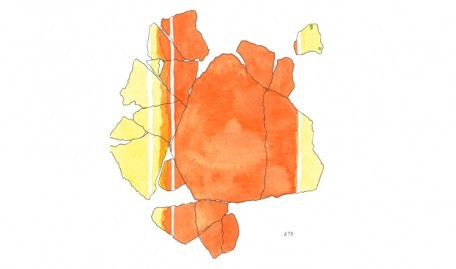

A large quantity of painted wall plaster was also found across the site, some fragments in direct association with the town house and mosaic, others with slightly earlier structures. A number of varied and colourful patterns can be discerned, giving some indication of the Roman taste in interior design.

Anglo-Scandinavian (5th to 10th centuries)

Evidence for occupation on the site in the immediate post Roman period (5th to 9th centuries) was slight, as is often the case in the lower city. It appears that stone from Roman buildings was removed during the late 9th or early 10th century, possibly after the buildings had been modified. There was some evidence of flooring, and a hearth was discovered close to the Danesgate frontage of the site. Evidence was discovered of Anglo Saxon bone and antler working, and a rare Viking soapstone vessel was found.

Medieval (11th to 16th centuries)

Ceramic finds from the site demonstrated that there had been occupation during the 11th and 12th centuries – immediately before and after the Norman conquest, and throughout the Medieval period. Finds included domestic debris such as animal bones, oyster and mussel shells and pottery.

A substantial Medieval stone wall was discovered at the southern end of the excavation, but the stone had been robbed at a later date, and the form and function of the building it was once part of remain unknown.

During the late Medieval period there is evidence of bone bead manufacture – a large quantity of distinctive pieces of animal bone with circular beads removed were recovered.

Tudor to modern (17th to 20th centuries)

The site was not heavily occupied in the 17th and 18th centuries. In the mid 19th century a series of terraced houses were constructed, fronting onto Flaxengate and Danesgate. By the late 19th century the site had even more housing and was the home of the Manvers Arms Public House which stood roughly where the cafe is.

The Victorian houses were destroyed in the 1960s in advance of the car park constructed in 1969, which immediately preceded the museum building.

Glossary

Canabae – an official civilian settlement outside of a Roman fort

In situ – the archaeological practice of ensuring that building works avoid archaeology rather than requiring it to be excavated, thus preserving it below ground

Samian ware – a fine red Roman pottery, made in southern France

Scheduled Ancient Monument – an area designated as being of archaeological importance, and which can only be disturbed with permission

Soapstone - a type of soft rock, often used by the Vikings for making cups and bowls

Tesserae – small cubes of stone or pottery used to make mosaics

Vicus – an unofficial civilian settlement outside of a Roman fort